This post is a part of a series of posts about iteration management. If you want to start from the beginning, go here.

The goal of capacity planning is to figure out how much work the team can get done in a given amount of time (usually an iteration). This will allow us to make sure we plan a reasonable amount of work for the iteration, and it will help us make a commitment to the business and actually keep the commitment.

It’s important to remember that we need to have a good reason for everything that we do, and we need to understand why we do it so that so that we only do the things that provide value. I feel that when people are afraid to try Agile, they are afraid of having to adopt a prescriptive process that dictates that they must do something in a way that is not the best way for their team. If we don’t know why we need to do something, we need to figure out why or start questioning whether it’s worth it.

The ultimate goal of most teams is to deliver working software, and to do it in a timely manner. The goal is not to cram in as much as possible, the goal is to move things through the system as fast as possible. We ultimately want to decrease the time between the time when a stakeholder thinks of an idea and the time when it’s live in production.

We also want to be able to predictably deliver software. Sure, your superior likes it when you get things done quickly, but if you make overly ambitious promises but then keep having to push release dates back, it doesn’t look good. This is where capacity planning comes in — we want to figure out how much we can realistically get done in a given period of time.

In order to do this accurately, you need to get really good at data analysis. This doesn’t mean that you need to go take a class in statistics, but it’s in your best interest to collect data and use it to your advantage. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve made an assumption about something related to software development and how long it takes, only to find out that I was way wrong once I looked at the data. That could be the difference in your project succeeding or failing.

Small

The magic word when it comes to capacity planning is small. Capacity planning gets easier as the tickets get smaller, the iteration length gets smaller, and the team size gets smaller. Remember that as we go through the rest of this.

Anyone who has ever tried to plan future work for a team of 10+ people will know what I’m talking about. It is possible and sometimes you get it right, but if your planning is off for even a couple weeks, you can waste a lot of time and money before you know it. But planning for two people? That’s much easier and your chance of being accurate is much higher.

Things to consider

Here are some things that I like to consider when doing capacity planning.

What the stakeholders want

This is obvious, right? When I say “stakeholders”, that could be “the business” or your user base (if you’re building/selling a product), or whoever is going to use the software that you’re going to build. What do they care about?

The word “stakeholders” implies that they have a stake in the game. So the first step should be to talk to whoever the stakeholders are and let them choose what you work on during the next iteration.

Keep in mind, that there could be multiple stakeholders, and they could include your manager, other teams, or your team. You might have technical debt that you really need to pay off.

Expected time off

Does anyone on the team have vacation coming up? Is anyone going to training for a day or two? Is there a 3 hour meeting coming up about health insurance benefits that everyone is going to attend? All of these factor into how much time each person has to spend each iteration.

Utilization %

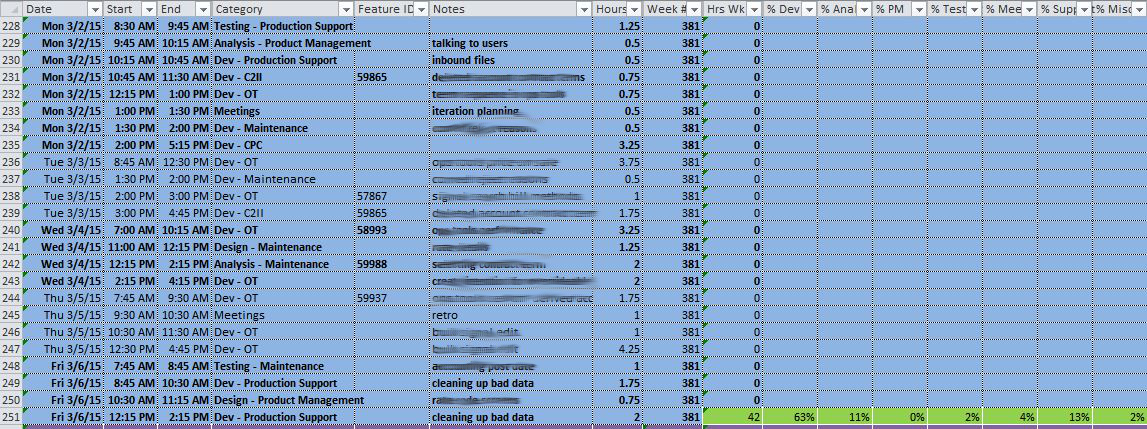

What percentage of each person’s time is spent on working towards completing tickets? No one spends 100% of their time working on tickets. We all have meetings, bathroom breaks, hallway conversations, and other things that don’t directly contribute towards moving tickets (however important they might be). I want to minimize the amount of this untracked time. Obviously, you want your people working on the task at hand instead of whatever distractions might come up, but I also want people to be creating tickets for things that come up during the iteration so that I can get a better picture of what goes on during an iteration (more on this later in the post).

Also, many people on the team, whether they notice or not, may perform multiple different functions. You might have a developer that does some testing, a QA person that does some analysis, and so on. So I don’t just want to know the percentage of time that goes towards moving tickets, I want to know the percentage of time spent on analysis, development, testing, and project/iteration management.

Normal working hours

Most employers assume a 40 hour work week, but that doesn’t mean that everyone works that. We’ve all worked with that person who puts 40 hours on their timesheet but works 50 hours. I’m sure employers and managers appreciate that person going the extra mile, but this really skews the capacity plan. If you use past iterations’ results as an indicator to help you predict how much work you can get done given a number of available hours, now you’re making assumptions off of data that isn’t accurate. What happens when the “dedicated” worker goes on vacation, or has something come up in his or her life and now they can’t work 50 hours anymore? You’re going to come up short.

I’m a big believer in sustainable pace and the idea that if we figure out how to work smarter in a reasonable amount of hours, we will outsmart and outpace the people who just throw more hours at a problem. I think of team members like washing machines — they work great, but if you put too much into it, everything they do needs to be redone. And of course, I want people on the team to have a good work/life balance. I want them to work hard, but I want them to enjoy their work and their life outside of work.

If you do have that person who wants to work extra hours for whatever reason, the important thing when it comes to capacity planning is that you’re aware of how much everyone is working so that you can factor that into your analysis. This means telling that guy who is working 50 hours to actually put 50 hours on his timesheet so that time doesn’t get lost for planning purposes.

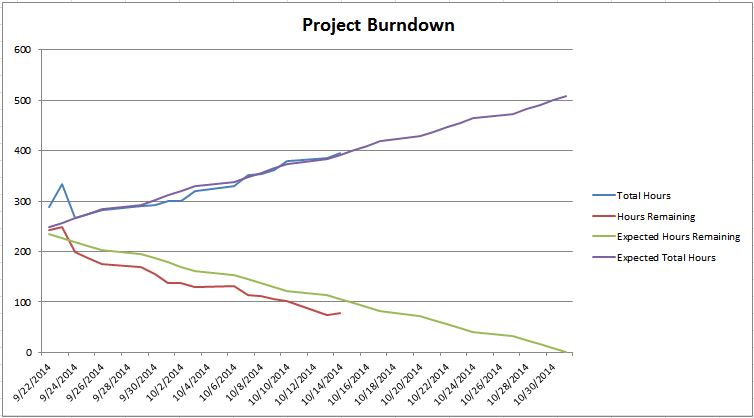

Work coming into the iteration

This is a big one. This can come from some obvious sources, such as production support, bugs found during the iteration, or new work that gets “discovered” when you realize that a certain feature needs some other things to be done in order for it to work. It can also come from less obvious sources, such as impromptu email requests for help, adhoc query help, or time spent having to help someone on another team. You want to track all of this.

I’ve started becoming ridiculously meticulous about this. You might think that it’s no big deal if you spend 1 hour writing an adhoc query for your boss and not creating a ticket for it, but now you have unaccounted for time where you were working on something and you don’t have a record of it. I’ve started creating tickets for this sort of thing when these come up just so that I can have a record of the time that I spent doing that task.

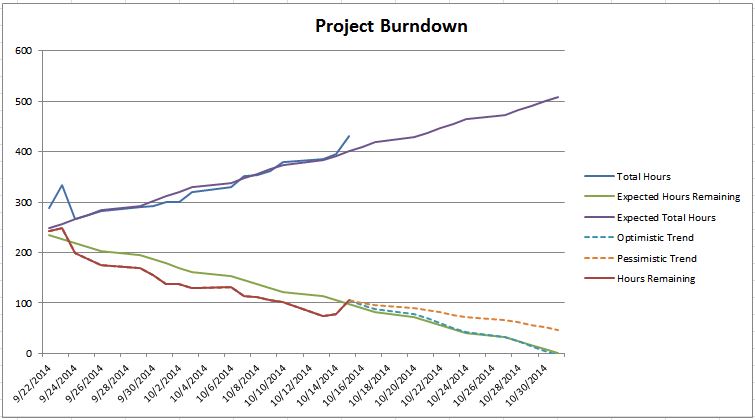

When I’m doing capacity planning, I run queries to find out how what tickets were completed in the previous iteration that were created after the start of the previous iteration and I total up the number of hours/points that were in those tickets. Over time, you will start to see a trend that will help you predict approximately how much work you need to account for that you don’t know about yet.

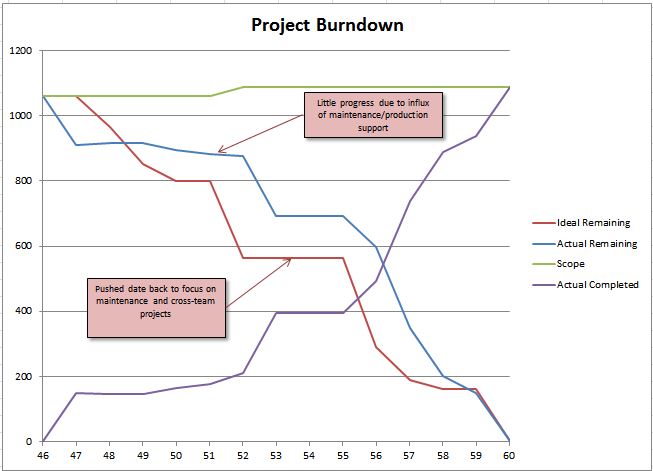

Getting this right can really be a life saver. Last year, the project I was on was constantly falling short of their iteration commitments and we kept having to push tickets out to the next iteration. This was frustrating people in the business because they didn’t actually know when things would get done, and they couldn’t do their own planning because they couldn’t count on us to deliver. When we started adding up the hours spent on work that came into the iteration, it was pretty clear why we weren’t able to get all of the work done — because we had other things come up that were deemed to be more important.

Agile people will tell you that work coming into the iteration is OK because the business can choose to swap out items for more important tickets at any time. This is true, but too often the work that comes into the iteration is a production issue or high priority item for someone in the business and this will negatively impact other people whose tickets get moved out (whether they like it not). There’s always going to be some amount of this, but I would rather try to minimize it by expecting the unexpected up front.

Multiple projects

In many cases, one team might be responsible for different projects of kinds of work. A common example is when one team handles both maintenance/production support and new features. If you have any division of work on your team, then you need to track time at the same level. For example, let’s say that you have 2 people working on production support and maintenance and 4 people working on new features. You’re basically doing 2 mini-capacity plans for 2 mini-teams at this point. This is actually a really good thing, because like I said before, the smaller the team size, the easier it is to plan.

Analysis and testing

A common trap that managers fall into is thinking that there is a linear correlation between number of developers and the amount of work that gets done. If you have two developers working on a project and you add a third, you aren’t necessarily going to get 50% more done because someone has to analyze and test that work. When you’re estimating tickets, make sure you also get estimates for the analysis and testing! This can be especially hard for business analysts because analysis is sometimes a somewhat nebulous activity that involves meetings, reading, writing requirements, and any number of other activities. Some estimate is better than no estimate, and this in the best interest of the person whose time is being estimated, otherwise they could end up with way too much work to do in not enough time, and that’s not good for anybody.

Another common trap is not leaving enough time to adequately test the work that is being done. The definition of “adequate testing” can vary widely, and depending on the situation, you might want to do more or less testing. But too often testing gets ignored and people only look at the development estimates when they do their planning (and remember, if you develop something on the last day of the iteration, you probably won’t have time to test it). Your definition of done should include testing, not just development. Remember, we are trying to figure out how much work we can complete in an iteration, not just write code for.

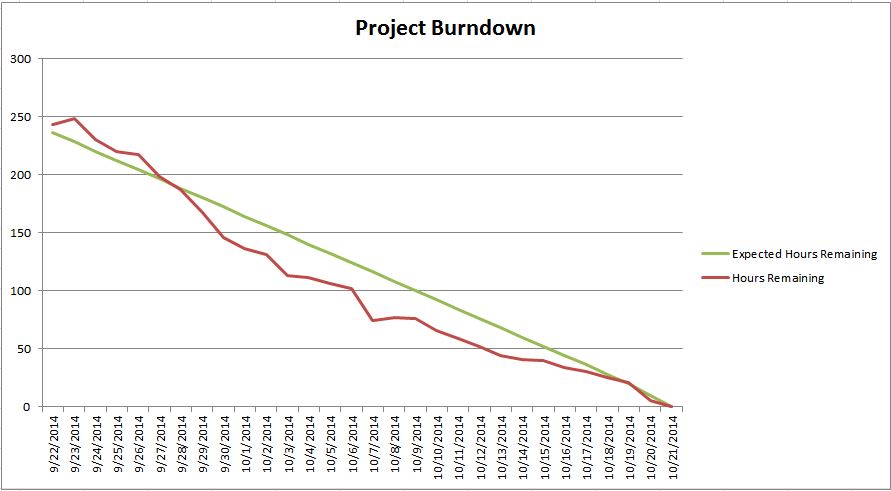

Past performance

Is the team consistenly over-committing (or under-committing)? Do you notice that someone on the team consistently over-estimates how much work they can get done each iteration? No one estimates correctly 100% of the time, and usually people tend to consistenly over-estimate or (more likely) under-estimate. Over time, your data will begin to paint a picture for you so that you can make the necessary adjustments.

Team consistency

Analyzing past performance is much easier if the team remains consistent. If you are adding or removing team members or if your team members can randomly get pulled off to work on other projects, your data from past iterations won’t be applicable and you’ll be a lot closer to flying blind.

You’ll be much better off by keeping teams intact and bringing work to teams. It’s OK to have one team responsible for multiple projects because you’ll do one capacity plan that covers all of them. But if the makeup of the team itself is changing, you’re job is going to very difficult. Teams tend to work better when they work with the same people over a longer period of time (not to mention it’s good for morale).

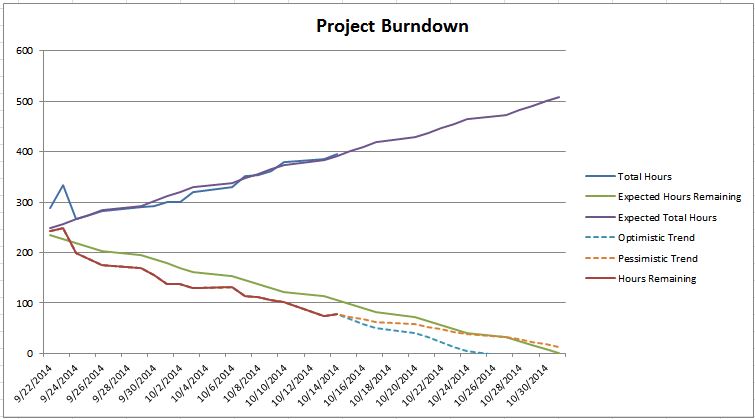

Gut feel estimates

So what if you have all of this data, how do you actually come up with a number of tickets/points/hours that a team can complete in the next iteration? Some people might advocate taking the average velocity over a significant period of time and using that as the estimate. If you feel that you velocity data is steady and reliable enough, then maybe that works for you. More often than not, that hasn’t been the case for me.

If your velocity data isn’t giving you an obvious answer, there are alternatives. If I’ve been on a project for long enough and I feel like I have a good grasp of things, then I might take a gut feel estimate of how much we can get done (velocity), but I’m also going to take a gut feel estimate of other factors, like amount of work coming into the iteration, % of time people spend moving tickets, % of time spent on analysis vs. development vs. testing, etc. Then at the end of the iteration, I can adjust my velocity estimate based on how accurate I was both on the large-scale estimate and the estimate I had for smaller, more measurable data points. Over time, my “gut feel” will become less of a gut feel and more based on several data points. I like this approach because I feel that it gets me to accurate capacity planning faster than relying on velocity, which we know can vary based on lots of factors.

The end result

Ultimately we want to come up with a list of features that we can commit to getting done in an iteration. Obviously everything is subject to change, but the more confidence we have in being able to complete what we’ve committed to, the better. Everything that I’ve talked about in this post to this point all points towards this goal, but the process to get there can be quite complicated. Over time, your team should be able to deliver quality work in a predictable manner, which makes everyone happy.

Read the next post in this series, Involving stakeholders.