This post is a part of a series of posts about iteration management. If you want to start from the beginning, go here.

As an iteration manager, it’s your responsibility to make sure that everyone on the team has what they need in order to do their job and complete the work assigned to the current iteration. This can be tricky, but I find that it’s the fun part of the job.

Get people talking

Once of the biggest hindrances to success is a lack of communication. I’m sure you can think of examples where a lack of communication hurt the team. Maybe a developer reinvented the wheel because he didn’t know about the existing way to do it. Maybe your testers had issues testing some functionality because they didn’t know how to use the app correctly when a developer could’ve quickly showed them exactly how to do it. Maybe the users were confused or uncertain about some of the changes that you were making because they had questions that needed answers.

Someone needs to make sure that people are talking. This doesn’t mean that you have to do all the talking, you just have to make sure that you get the right people communicating so that everyone is on the same page.

An easy way to do this is to get the team members to sit together. This sounds obvious and many teams have at least part of the team sitting together, but it really helps having the BAs, developers, and QAs in the same area. Yeah, we might have email or instant messaging or phones, but people communicate so much better when their working in the same area. Plus, it increases team camaraderie, which helps communication even more (and it’s fun).

Be the unblocker

It’s your job to be the unblocker. This doesn’t mean that you just remove blockers for people, you also need to be able to see when people might be stuck and help them to get unstuck again. What complicates this is that many people don’t want to ask for help. They might think that they should be able to figure it out on their own, or maybe they don’t want to inconvenience people.

Whatever the excuse, there are usually some telltale signs that you can spot. Maybe you don’t see progress on something that should be moving along, or maybe you hear people sounding frustrated and complaining that they’re having trouble with something. This is where your intuition comes in.

Your job is to do whatever you can to allow people to focus on the work that they need to get done, which is what people tend to want to do anyway. But sometimes someone needs to see that there’s a problem and get the right people in the room to talk about it.

Sufficient requirements

I’ve been on projects that have really well defined requirements and many others that didn’t, and let me tell you, it makes a huge difference. If your requirements are only 80% complete, then your developers are probably going to get it 80% right. When QA goes to test, they have questions about the requirements just like the developers did, and they either write up bugs or get in arguments with developers about how things should be.

When the requirements are well defined, you don’t have as many of these problems. In fact, you probably shouldn’t start working on a feature until you’ve all talked through it and make sure that everyone agrees on the requirements (which include the acceptance criteria).

What counts as “sufficient requirements”? That’s up to you. There are some cases where I feel like I need to write part of the code so that I can find all the things that I’m not thinking of. If I do that, at some point I’ll have a better understanding of what the requirements should be, and then we can meet about it.

What I don’t want are people not knowing how something should work, or people feeling like they need to make assumptions or decisions about how things should work, or people having to wait for requirements clarification. When things are well defined, everything tends to go smoothly because people don’t have to worry about not having all of the requirements and they can just work.

Keep things flowing

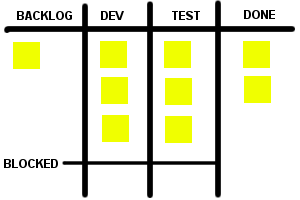

You can only move as fast as the slowest part of your process. Here’s how this often happens: management wants to get things done faster, so they come to you and say, “Let’s get more developers!” That’s great, but if you don’t have someone to write requirements for that developer or help test their work, things aren’t going to move any faster (or maybe they will at the expense of quality).

If even you aren’t in that situation, it’s virtually impossible to always have perfect balance of analysts, developers, and testers, especially on smaller teams. What do you do if you have 1 analyst, 3 developers, and 2 testers, but suddenly you really need 2.4 testers? The only way to get 0.4 of a tester is to have someone else on the team that is not in tester role help out with testing. This is where it’s extremely valuable to have people that can do several different roles well so that you can eliminate bottlenecks in the process and keep things flowing.

This especially applies to developers, because often times the bottlenecks happen when developers get work done faster that QA can test it (and many teams have a shortage of testers anyway). I like to encourage developers to learn how to do other tasks, like analysis and testing. This can help eliminate bottlenecks, and it makes developers better contributors in general. In some smaller teams, the developer is also the analyst and the tester and needs to know how to do these jobs.

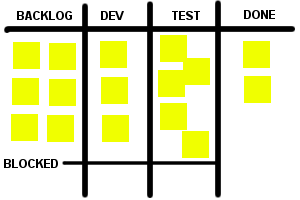

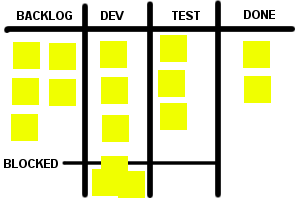

Finding the bottlenecks

How do you find the bottlenecks in the process? This is exactly why we have big visible boards for tracking work items instead of just using online tools! It also helps if you break your tickets down into smaller tickets so that you can actually know when things get stuck. If all of your work items take a week long and three days in your developer doesn’t really have much to show for it, are they really behind or do they just need to hook everything up so that you can see it work? You don’t really have a good way to tell (other than asking and hoping that the developer can accurately and honestly give you the right answer).

We also want to find waste in the process. Usually this comes in the form of waiting. For example, waiting for answers from the business on requirements questions, waiting for testing environments to get fixed so that testing can start, waiting for management to make decisions, or any number of other problems. It’s impossible to eliminate all of these, but we can try to reduce them by communicating and finding creative ways to make things move better.

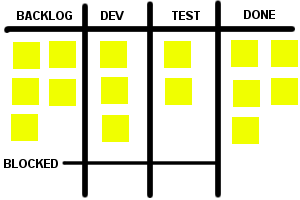

Finishing

Think of the end of the iteration like a release date. Maybe you will actually be releasing to production. Either way, the goal is that functionality that goes into the iteration gets done. And by done, I mean all the way done. That means, that it’s developed, tested, and the users want to sign off on it. If you have another definition of done, you might be lying! When management hears “done”, they think that you don’t have to do any more work on it. So if you still have more work to do, that’s time that they aren’t accounting for in their mind, so now you’re in a tough spot.

As you get towards the end of the iteration, you need to make sure that everything that is going to be developed this iteration also can be tested by the end of the iteration. If you want to get a feature done by the end of the iteration, you can’t have developers checking in changes on the last day of the iteration if QA needs 2 days to test it because they won’t have enough time. On our two week iterations, usually we are cutting off checkins a day or two before the iteration ends, depending on how QA is doing. Developers might even help test if QA gets behind and can’t get it all done. Typically that doesn’t happen, so developers can keep working, but maybe they don’t check their code in until the iteration is over (or check it into a branch). This ensures that the QA team has enough time to test everything that is going into the iteration.

Be creative!

Every project is different, and every project will have it’s own unique set of problems, many of which you have never encountered before. At this point, your intuition needs to take over. Don’t underestimate the value of intuition and common sense! You can read all the books and blog posts that you want, and many of those will have good ideas, but it’s up to you to apply the ideas and tailor them for your situation.

Read the next post in this series, Estimates.