Every business cares about making money and reducing costs. Yet every day I press a button and sit idly while I watch a little progress bar move. This happens every time I want to run an application or run a test.

Compiling code is something we’ve just gotten used to. Maybe that’s not the right phrase — we’ve learned how to put up with it. Granted, things are a lot better than they used to be. My first job after college was working on a C++ application where changing some of the foundational header files meant 30 minutes of compiling just to rebuild the application!

When .NET came out, they said that it compiled so fast that you would wonder if it actually did anything. That was true on demo apps that only had a few source files, but as your application grows and grows over time, those compilation times are quite noticeable. Certainly it was better than it was in C++, but that only makes you feel good for so long.

Let’s compare this to working with a dynamic language like JavaScript. When I’m coding JavaScript, it runs my tests in less than a second whenever I save a file!! No compiling, no loss of momentum, and oddly enough, dynamic languages don’t run noticeably slower than compiled languages for the kinds of applications that most of us are building.

Scary math

How much is compiling costing you? I decided to find out. The application that I’m in is 5 years old and has a fairly sizable codebase. Rebuilding the entire solution takes about 2 minutes, but usually I don’t need to rebuild everything. If I change a test file and run the tests, it still takes 30 seconds to compile what it needs to run the test. My machine is a year or two old, but it’s a pretty solid development machine with plenty of RAM and everything running on SSD. Your codebase may be smaller (or larger) than mine, so the compile times will vary. If you codebase is smaller because you app is younger, think about what it might be when your app is 5 years old.

There is a Visual Studio extension called Build Monitor that will record the compilation time every time you compile and then dump it to a json file. We all installed this and we recorded compile times from several different developers over a couple weeks, and here’s how it came out:

99 hours of dev time

5.4 hours spent compiling

… which means that 5.45% of our time was spent waiting for the code to compile.

Let’s put this in perspective:

If I code for 8 hours, I lose 26 minutes to compiling each day.

If I code 6 hours a day on a 6 month project, I lose a whole week to compiling.

Spread that across your entire team and multiply that by the average hourly rate of your employees.

5 days lost x 6 hours of coding time per day x 5 devs x $60/hr = $9,000

That’s real money!

Note that we haven’t taken into account that I can’t take advantage of my tests as much when the cost to run them is higher, so I’ll write a bunch of code before I run the tests, which makes diagnosing problems harder.

We also aren’t taking into account the slowdown that comes from having to stop for 30 seconds and go find something else to do like check email while I wait.

We also aren’t taking into account the lost business value because we can’t deliver features faster.

We also aren’t taking into account that someone out there is writing code that is trying to take away your market share, and if they can do it faster than you, they have an advantage.

What can we do about this?

Here are some things you can try to reduce compile times.

Get an SSD

There’s absolutely no reason why you should not be using a solid state drive at this point. When I switched to an SSD, my code compiled 3 times faster. You can get a 128GB SSD on Amazon for under $50. If your company won’t buy one for you, buy it yourself.

Get a faster machine

A new machine isn’t as cheap as an SSD, but if you can get a faster machine and speed up compilation time, the machine is going to pay for itself very quickly. At least make sure that your current machine isn’t strapped for RAM (which is really cheap).

Check your build settings

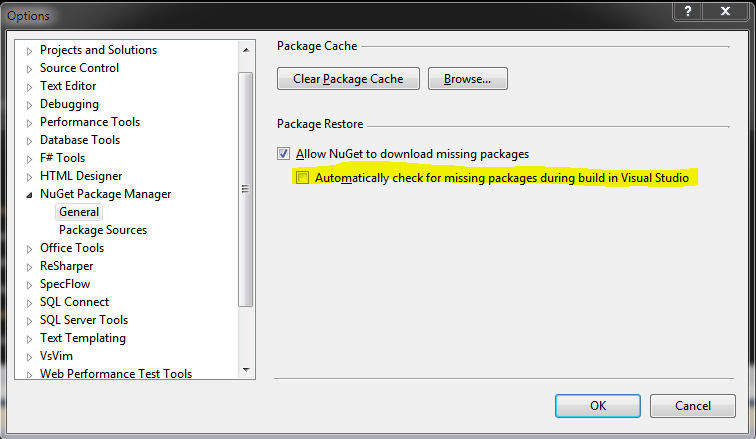

Once you download your nuget packages, you don’t need to check for them on every build! I like to leave this box unchecked.

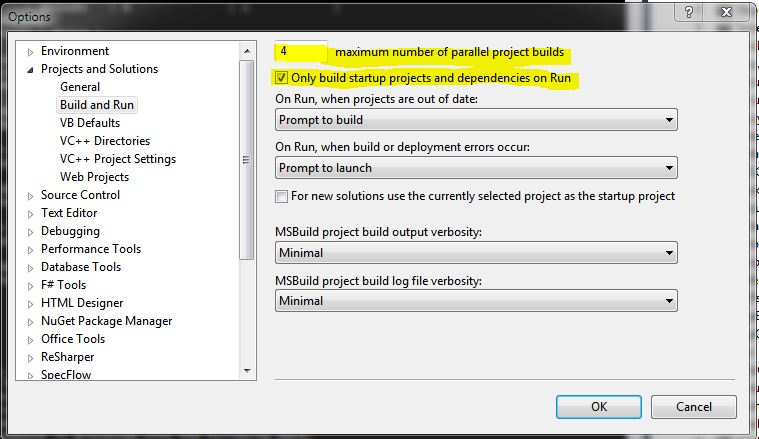

Make sure the number of parallel project builds matches the number of threads your machine can run at one time. Also, when you run your code, you should only be building the projects that you need to run the code.

Split up your solution

If your solution contains a bunch of projects that you don’t ever edit, they’re just taking up memory and compile time. I like having one solution that has everything, but it can’t hurt to make smaller solutions that only have subsets of the code that you need in certain circumstances.

Unload projects

If you don’t split up your big solution, you can unload projects by right-clicking on the project in the Solution Explorer and selecting Unload Project. This will essentially remove the project from the solution that you have open without actually removing it (unloading is a user-level thing, so you can unload what you want without affecting your other team members).

Consolidate projects

I see lots of solutions where there’s a project for the data layer, a project for the business layer, a web project, and many more. The problem with this approach is that every time you compile, it has to copy .DLLs around to all of those different bin\debug folders, which takes time.

I would recommend consolidating projects whenever you can. Yeah, this might allow someone to reference the data layer from a controller instead of going through the business layer, but we all should know what you should or shouldn’t do in a codebase without having to have project boundaries enforcing it.

There is one caveat here… if you consolidate projects, then you can’t unload them anymore and you’ll have to compile them all the time. So while you might save time by consolidating projects, in some cases you could increase people’s compile time because you force them to compile code that they might otherwise unload.

Rethink your language choice

If you’re using a dynamic language like Ruby or Python or JavaScript and you’re still reading this, you may be mocking .NET developers right now. People that use dynamic languages can run their tests anytime they save a file. They can deploy changes to code by just deploying a single code file instead of compiling all of the code and deploying it. They can change a line of code, hit F5 in the browser, and immediately see what will happen. They don’t have to spend $500 for their IDE. They don’t absolutely need to have super high end machines to do development. And oh by the way, they aren’t spending 5% of their day watching their code compile.

(Yes, I know there’s a free version of Visual Studio, but how many of you are using that at work?)

I did Ruby on Rails for a year, and not only was it nice to not have to compile, I just loved the language. You really can do a lot more with less code. I felt like someone took off the training wheels and I could just write code that did what I wanted to do without all of the ceremony.

I realize that it doesn’t make sense for most teams to rewrite an existing codebase in another language just to avoid compilation. However, I will say this – someone else is competing against your company, and by using another language, they could have a 5% (or more) advantage. Ruby on Rails is very widely used by startups, and no one is more pressed for time and money than a startup.

C’mon .NET

I’m sure there are reasons that .NET can’t become an interpreted language like Ruby, but why can’t it? You can already make dynamic method calls in .NET using reflection, and at runtime it will attempt to call the method that you specified and will throw an exception if it can’t find the method. So why can’t everything work that way? Compilation may still have value as a sort of test to make sure that everything does link up, and it probably makes runtime faster if I can compile my code before I deploy it. But the real win will come when I can write .NET code and run it without having to check every method call and check every line for syntax errors when I’m only going to execute a few lines of code in a test.

Yeah, I know, now there’s ASP.NET Dynamic Compilation, but when I read about it, it just sounds like moving the slow compilation to the web server, which is convenient but isn’t going to save a lot of time when developing from what I can tell. But I haven’t actually tried it, so I suppose I could be wrong (I hope I am).

What else am I missing?

Do you have any ideas, tips, or tricks for how you’ve reduced compilation time on your team? I’d love to hear your thoughts! We’re all tired of watching progress bars.