There are those who believe that a developer should not test their own code. This may sound logical, but I’m not sure I’m buying it.

This statement typically refers to QA testing, and doesn’t mean that a developer shouldn’t write unit tests. The thinking here is that a second person testing the features that you’ve developed might think of things a different way and find a problem that you didn’t think of when you wrote the code.

There are lots of commonly accepted statements and ideas like this in software development. But I’ve found that in many cases, these ideas are usually based on certain assumptions, and if you can challenge those assumptions, you might open yourself up to things that you didn’t think were possible.

The assumption that I see here is that a developer writing the code is not sufficiently capable of thinking of all of the test cases. Imagine you write code for a feature, and now you have to test it. At this point, you’ve gone through a certain mental thought process when you implemented the feature. This makes it much harder to think outside of the box to come up with the edge cases. Not to mention that when you see that the feature appears to be working overall, it’s really really tempting to do some basic manual testing and then move on to the next feature without really doing your due diligence. A independent QA tester, however, will look at the feature objectively because their thought process isn’t clouded by past experience of having written the code.

OK, so what if the developer figured out all of the tests cases before writing the code? Now their thinking isn’t clouded by the implementation of the feature because they haven’t wrote the code yet. Maybe a QA person helps define the test cases, but this post is about developers testing their own code, so let’s assume that QA people aren’t involved. I would argue that now we’ve removed the main reason that developers are not good at testing their own code (thinking of the test cases after writing the code), so they should be able to think of test cases just as well as a QA tester, and therefore they should be able to test their own code.

Don’t misconstrue what I’m saying there – I’m not saying that we don’t need our QA teams. I’m saying that developers need to be responsible for testing. QA teams can add more testing help, but developers need to be responsible for their own code.

This opens you up to new possibilities. It enables developers to be confident about the quality of their code. It limits the wasted time you incur when you have the back-and-forth that comes with QA finding bugs and developers having to go back and fix things. It can reduce the amount of “checking” that QA people need to do because they might be comfortable knowing that developers are writing quality code.

If you’re a developer, this is some thing you can start doing today. Before you implement a feature, come up with all of the test scenarios before you write your code. If you have a QA team, have them review your test cases to see if you’ve missed anything. Then go write some bug free code!

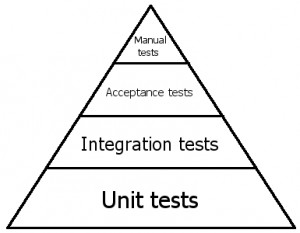

You may have also seen the automated testing triangle diagram, which illustrates how you should have more unit tests than the other kinds of tests and how the unit tests are the foundation of your test suite.

You may have also seen the automated testing triangle diagram, which illustrates how you should have more unit tests than the other kinds of tests and how the unit tests are the foundation of your test suite.