I’ve always said that software development is a series of translations — that we need to incrementally translate business processes to business requirements to acceptance criteria to test plans to tests to code to working software. This is why we write acceptance criteria in the Given/When/Then syntax — it’s a common language that developers, BAs, testers, and business people can use to make sure that we’re all speaking the same language. These kinds of requirements define what the system is supposed to do for the business.

All this is good, but there still are problems. Let’s say that your BA writes some requirements and you implement a feature. Several months later, you get a new requirement to change that code, or someone asks you what the code does for a certain feature. How do you find the code for that feature?

Or maybe you have some common validations that happen many times throughout the application. Are your BAs copying and pasting the rules for that validation over and over in the requirements documents?

What seems to be missing here is another layer of translation. We have too big of a jump from our typical business requirements to our code, and no way to map the two to each other. The acceptance criteria tell us what the code should do, but nothing tells us how to do it.

On my current project, they’ve come up with an ingenious way to solve this problem. (I have to preface all of this by saying that none of this was my idea and I can take zero credit for it. They were doing it long before I joined the team.)

Our system does transaction processing with incredibly complicated business rules. All operations are written as command classes and workflow classes (which are a series of commands).

Our requirements are structured the exact same way. In the requirements we have commands and workflows that are named the same as the classes in the code.

Example

Let’s say I’m building an order processing system. Here’s how we might break it all down.

High-level business requirements

When an order is processed, the order total is sum of the cost of the products + tax + shipping. Save the order information and the total price to the database.

Tax depends on where the order is being shipped:

Ohio – 7%

Michigan – 6.5%

Any other state – 0%

Shipping:

If sum of the cost of the products >= 25, shipping is free, otherwise $5.

System requirements

Workflow: Process Order

1. CalculatePriceOfProducts

2. CalculateTax

3. CalculateShipping

4. SaveProcessedOrder

Command: CalculatePriceOfProducts

Total Price = sum of price of each product on the order

Command: CalculateTax

Tax is calculated based on state the order is being shipped to. Can ship to US states only (including DC).

Ohio – 7%

Michigan – 6.5%

Any other state – 0%

Command: CalculateShipping

If total price of products in the order >= 25, shipping = $0

Otherwise, shipping = $5.

Command: SaveProcessedOrder

Save the following information to the database:

– Products in the order (save current price in case the price of a product changes after the order has been processed)

– Tax amount

– Shipping amount

Acceptance tests

We’ll write unit tests for each command. There are 153 different combinations of shipping (>25, =25, <25) and tax (51 states), so our unit tests will cover all of the permutations. We’ll write acceptance tests to cover some of the most likely scenarios.

Scenario: multiple products with total < 25, shipped to Ohio

Given an order with the following products:

| Product | Price |

| Mouse | 4.00 |

| Keyboard | 20.99 |

And the order is being shipped to Ohio

When I process the order

Then the tax should be $1.75

And the shipping should be $5.00

And the total price should be $31.74

Scenario: one product with total = 25, shipped to Michigan

Given an order with the following products:

| Product | Price |

| Mouse | 25.00 |

And the order is being shipped to Michigan

When I process the order

Then the tax should be $1.63

And the shipping should be $0.00

And the total price should be $26.63

Scenario: one product with total > 25, shipped to Indiana

Given an order with the following products:

| Product | Price |

| Mouse | 25.01 |

And the order is being shipped to Indiana

When I process the order

Then the tax should be $0.00

And the shipping should be $0.00

And the total price should be $25.01

Why this is awesome

This has made everything so much easier for everyone. Developers and system analysts can easily communicate because we speak the same language. When we get new requirements that change existing code, the systems analysts even specify which commands and workflows we need to change. Now I know exactly where I need to go to change code without having to do any research!

Duplication is bad in code and it’s bad in requirements. When a new workflow needs to be created, they can reference existing commands without having to copy and paste requirements. The commands and workflows are in a big Word document with links so that I can easily navigate around the document.

Because all of the commands and workflows are outlined before we write the code, most of our design work is done for us. I know what classes I need to create. I know the specific things that each command needs to do, and I can easily unit test them. We have some older code in our application from before they switched to writing requirements in the command pattern. These classes tend to be too big and they’re much harder to decipher, partially because I can’t easily figure out how they map to the requirements. Every time we encounter one of these, we want to refactor it to match the requirements.

Estimation has become a lot easier. I can look at each command in a workflow and get a sense of how hard each one is (or which commands are existing commands that I can reuse), and I already know how I’m going to design my code for the most part.

Keeping requirements up to date is a challenge on any project, but this has helped us do a pretty good job of it. But when you have well structured requirements that don’t have stuff copied and pasted all over the place and you can easily compare a class and a section of the requirements with the same name, updating requirements becomes a lot easier.

The command pattern is a good fit for our application, but your app might not lend itself to the command pattern as well as ours. That’s fine, see if you can come up with another pattern if you want. But sit down as early as possible and see if you can come up with a way to structure your requirements and code using the same patterns.

As you can see in the example, we still have acceptance criteria in the Given/When/Then format. The acceptance criteria help define what the system is supposed to do and how we’re going to test it. The business requirements that we write in the command pattern define how the system is going to accomplish those goals. This method has filled that translation gap between business-focused requirements and code and has had a huge impact on our project.

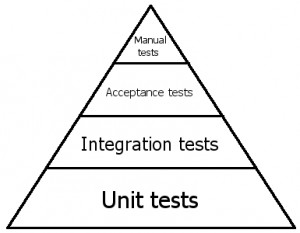

You may have also seen the automated testing triangle diagram, which illustrates how you should have more unit tests than the other kinds of tests and how the unit tests are the foundation of your test suite.

You may have also seen the automated testing triangle diagram, which illustrates how you should have more unit tests than the other kinds of tests and how the unit tests are the foundation of your test suite.