This post is a part of a series of posts about iteration management. If you want to start from the beginning, go here.

One thing that you’ll find on pretty much every Agile project is some kind of card wall where features are tracked.

When I started working on Agile projects several years ago, I didn’t quite understand the purpose of the card wall. I thought, wouldn’t you rather just track everything in some online tool?

While tracking things in an online tool is still a good idea, the Agile card wall gives you a level of transparency that it’s difficult to get from an online tool. With a good card wall, you can easily see what everyone is working on, what still needs to be worked on, how long the remaining work might take, and what’s blocking your progress. There is so much to keep track of on a software project, and it really helps when you have a visual aid that can help keep everything in front of you so that you don’t have to juggle everything in your mind (or some online tool).

The trick is to tweak your card wall to give you the most transparency as possible. Here are some things that I’ve found help me get the most of my card wall.

Everything is a task

Everyone puts development tasks on their card wall. However, not everything that your team does could be categorized as a deliverable feature. In fact, there are lots of other things that you might have to do:

- Write up documentation on a wiki

- Onboard a new team member

- Set up a CI build

- Get ready for a demo

These are all tasks that are completed by development team members that take a measurable amount of time. So why not create a card and put them on the board? Maybe you use a different color card to indicate that it’s an internal task. This gives you two benefits — you know what people are working on and you can use the estimate to gauge how much work is left to be done.

Make card walls for your entire team

If our development card wall can help us track what developers are working on and how much work is left, why not create card walls for the entire team? You could have a card wall for BA requirements gathering, QA creating test plans, project management tasks, or some mini-project that you want to track separately. You get the same benefits that you get with a development card wall — you know what people are working on, you can easily see the status of the effort, you can prioritize the backlog, and it can help you get an idea of how much work is remaining.

Make problems obvious

Your card wall should alert you to any problems and blockers as soon as possible, so that you can remove any blockers and constraints that could keep your team from being able to do their job. Some ways that you can do this:

- Create a separate section of your card wall for blocked items

- If something is blocking a feature, put a post-it note on the card and write what the blocker is

- Structure your card wall so that you can see problems immediately just by glancing at it

Let’s look at some examples of some simple card walls and we’ll interpret what we see.

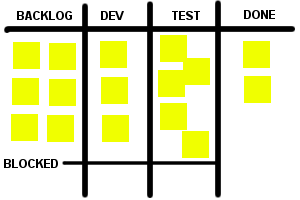

Example #1

In this example, we can easily see that we are either developing things faster than we can test them, or things are getting stuck in testing due to bugs. We may need to assign more people to testing or work on reducing bugs.

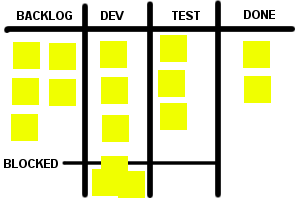

Example #2

There are a lot of features that are blocked. We should try and address the blocking issues and look and see if there is some greater problem that is causing things to get blocked. Maybe we need to write better features, or maybe we need to get more time from people in the business who can answer questions.

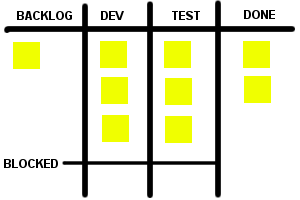

Example #3

We don’t have much in our backlog, so the developers are going to be out of stuff to do really soon. We may need to get more people working on requirements gathering.

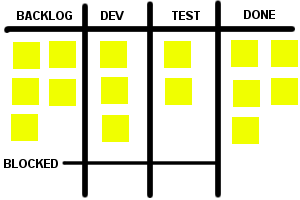

Example #4

Things are flowing pretty smoothly. We have a good sized backlog, no blockers, the work is evenly distributed, and we’re getting a lot done.

The key is that we want to see problems as soon as possible so that we can take the necessary steps to correct the problem and keep things moving.

Address technical debt as part of the process

As much as we hate to say it, sometimes it makes sense to shove in lower quality, untested code in order to meet a deadline. I don’t like having to do this at all because of the risks, but when this happens, keep track of all technical debt that will need to be fixed and create separate cards for fixing it. Make these cards a different color so that they stick out. Then use your board to explain to your manager or project sponsor that you’re going to need some time to go back and fix the technical debt. Many managers want to pretend that the work is done once you release and will convince themselves that they can just move on without addressing the technical debt. You know better, and it’s your job to state that case and show why it’s important.

Refactor your card wall

Your card wall is yours. You create it, you manage it, and it belongs to you. Don’t be afraid to rearrange and refactor your card wall so that it can better meet your needs. Don’t make excuses like “we’ve always done it this way” or “we read a book that said to do it this way” or things like that. Your process and tools need to serve you not the other way around.

Read the next post in this series, Managing the iteration.

On some projects, the team is testing a big black box. Usually this is where QA people are doing all the testing and developers aren’t writing automated tests. If you read my blog at all you know that I do not like this approach (unless time to market is really that important) because it leads to lots of bugs and makes refactoring anything really scary. In this scenario, QA testers typically only control the inputs and outputs into the black box (which is usually a user interface of some kind). This leads to problems like having to jump through a bunch of hoops just to test something that’s farther down the line of some complicated workflow.

On some projects, the team is testing a big black box. Usually this is where QA people are doing all the testing and developers aren’t writing automated tests. If you read my blog at all you know that I do not like this approach (unless time to market is really that important) because it leads to lots of bugs and makes refactoring anything really scary. In this scenario, QA testers typically only control the inputs and outputs into the black box (which is usually a user interface of some kind). This leads to problems like having to jump through a bunch of hoops just to test something that’s farther down the line of some complicated workflow. If you’re a fan of test-driven development, you will write a lot of unit tests. In this case, you’re slicing your application up into very tiny, testable units (like at a class level) and mocking and stubbing the dependencies of each class. This gives you faster, less brittle tests. You still probably have QA people testing the black box as well, so now we’re using two different approaches, with is good.

If you’re a fan of test-driven development, you will write a lot of unit tests. In this case, you’re slicing your application up into very tiny, testable units (like at a class level) and mocking and stubbing the dependencies of each class. This gives you faster, less brittle tests. You still probably have QA people testing the black box as well, so now we’re using two different approaches, with is good. There is no one-size-fits-all method for testing applications, and there isn’t even one single best way to test a single application. So what if we used many different approaches and broke our system up into chunks so that we can use each testing method to its fullest potential?

There is no one-size-fits-all method for testing applications, and there isn’t even one single best way to test a single application. So what if we used many different approaches and broke our system up into chunks so that we can use each testing method to its fullest potential?